«How many lathes and how many metres of fabric will this triumph yield!»1 – Football and Planned Economy Propaganda in Hungary during the Rákosi era

This article examines the ways in which popular footballers and football

successes were used to propagate the planned economy system in Hungary during

the communist dictatorship. The paper therefore explores the political and

social role of football, as well as its popularity in Hungary and the most

important attributes of planned economy. The analysis investigates the ways in

which footballers were used by the government and how they were portrayed by

the press. In doing so, it addresses specific questions: what features of

footballers were presented as a role model? How did the political leadership

try to encourage people working harder, using the national team’s 6:3 victory against England in 1953 and how did the idea of the “6:3 shift” emerge? How could football be used to promote the “peace loan subscriptions”? Furthermore, the author discusses whether the hungarian reality matched the

propaganda.

Keywords

: football, communism, planned economy, Hungary, Golden Team

1. Introduction

In my study I am investigating the relationship between football and planned economy propaganda during the communist dictatorship of Rákosi after World War II. I would like to demonstrate how the most popular footballers of the period and the most important football victories were used to promote the success of the planned economy 2 . Why was the press trying to portray top-class footballers presented as idols to the society by the communists as “masters of work”? Which features of the football players were shown to the people as examples to follow? In what ways were bigger football events used for the purposes of economic propaganda? In connection with which political events and measures of the planned economy were the best footballers used? How was all this presented in the press propaganda? And last but not least: to what extent did these propaganda materials correspond to the reality?

In many cases the political leadership used the outstanding results of popular footballers to prove the socialist system’s “supremacy” over the western system with the help of propaganda methods 3 . The economic aspects are less known and apparent, so it is necessary to elaborate these 4 . This will constitute the focus of my study, to expand on other elements of political use is not within the scope of the present paper.

First I would like to outline the reasons for the unique popularity of football and the main elements of the master of work-Stakhanovite movement. Then I will carry on to describe the economic propaganda related to top-class footballers. For the presentation of the planned economy of the socialist system and Stakhanovism I mainly relied on English language literature. For the further parts of the study discussing the propaganda I mainly used Hungarian press articles from the period, in some cases archive materials. The interpretation of the propaganda and its comparison with reality was based on memoirs, interviews with renowned sportspeople of the era and publications about the connection between football and politics.

2. The role of football at the time of dictatorship

After losing the Second World War Hungary became part of the Soviet sphere of interest. The dominance of the Communist Party 5 gradually increased on a political and social level as well. Finally in 1948 based on the Soviet Stalinist system the era of repressive one-party dictatorship started with the leadership of Mátyás Rákosi, general secretary of the party 6 .

Though football had been a popular sport also before, during the Rákosi era it considerably received more social and political attention than any other sport or leisure activity in Hungary 7 . This extraordinary attention 8 from the people can be explained as follows: I. The lack of other types of entertainment. After the World War II the country was in ruins. Television and the beat movement were not yet present in Hungary, poor children played football from dawn until dusk in villages and in empty parts of cities - partly created by damages caused by the war. Visiting football games on the swiftly restored football pitches was one of the most popular pastimes of all age groups. II. Football as opportunity for advancement. Star footballers who had a much higher standard of living than average people, became almost folk heroes, many children wanted to become wealthy and famous football players. III. Football as sports experience. It was a uniquely successful period of Hungarian football, spectators could see top-class European footballers in the stadiums, even in smaller teams. IV. Football as substitute for success and space for national emotions. In the suffocating world of communist, with its state terror and its work competition campaigns, football provided Hungarian people a collective source of happiness and a substitute for success in a unique way 9 . The successes of their favourite team could make people temporarily forget the horrors of everyday life. After two world wars and losing two thirds of the country’s territory and more than half of its population, even though within the bounds of a communist dictatorship, the outstanding successes of the national football team gave people the opportunity to see their nation as successful and be proud of it. V. The football pitch as a community space. The communist dictatorship, in order to weaken social cohesion, made every possible attempt to destroy small communities, therefore it also tried to strip sport clubs of their sense of identity and their symbols 10 . In spite of this traditional meanings, often deemed as harmful by the regime, continued to exist and fans belonging to close-knit communities of supporters defined themselves according to these just like before. VI. The football pitch as a field of free speech and action. Those years any statements that were considered enemy could get people in prison, but in the stadiums, “hiding in the crowd” people could express their opinions more freely, even in political matters 11 .

Football was important for other reasons for the leaders of the regime as well. Paradoxically, football became attractive to the regime because the crowds were seeking refuge in the world of football - partly due to the communist terror. The largely unpopular party saw football as a legitimation tool serving to consolidate its power. They transformed the system of sports associations, making football clubs the symbols of communist ideology in their names and coats of arms 12 . The huge crowds present at the stadiums created a sense of illusion of a consensus between the people and the regime similarly to marches and parades. The outstanding sports successes, defeating England and other developed western countries, became part of the propaganda: the communist ideology attributed the victories to the efficiency of party politics. In their interpretation the triumphs proved the supremacy of socialism over the capitalist system - in a political, social and economic sense as well.

According to James Riordan, in communist states all over the world sport was mainly used for the following purposes: “nation-building” and “integration”, that is uniting the society based on the egalitarian nature of sport, “defence”, that is the militarization of the society with the help of sport, “health and hygiene”, “social policies” and achieving “international recognition and prestige” 13 . These aspects also appeared in Hungarian sport politics, in connection with mass sport and professional sport 14 . From the point of view of my topic - the study of the “top-class athlete master of work” - the more significant categories defined by Riordan are ‘nation-building” and “integration”, though they do not exactly describe the situation in Hungary: nevertheless, since the portrayal of top-class athletes and top-class footballers as workers was supposed to demonstrate their leading position of the working class and since, during the years of heavy industrialization, a significant urbanization was also taking place, it can be considered as a kind of conscious integration attempt as well. As examples given in my study will demonstrate, football can be seen as a kind of social policy and an attempt at achieving international recognition through the results or even the physical defence of the country.

The most effective tool to achieve the above mentioned political goals was the propaganda that mainly used the press as its platform in the period. The most popular daily sports newpaper, the «Népsport» ( in English: «People’s Sport») conveyed messages embedded in sport and football. The following is a quote from the secreterial papers of the minister of defence Mihály Farkas, an important figure in the sport life of the nation 15 :

Why is sport press important in the political education of the masses? Because sportspeople and the sport-loving crowd are mainly apolitical, neutral, even (...) slightly hostile towards democracy. This crowd cannot be convinced with purely political tools since you cannot access it. They definitely read sports newspapers because they are interested in sports and once they have bought the sports paper they will read the political articles in it because they are related to sports. (...) This is the only way these sport-loving people can be approached 16 .

During those years sport was much more than a simple game in Hungary. On 25 November 1953 during the legendary England-Hungary match and later during the games of the 1954 World Cup life literally stopped in the country, streets became empty, almost everyone listened to the broadcast of the radio reporter György Szepesi 17 . In the following part of my study I would like to describe how the regime tried to use this exceptional interest for the purposes of economic propaganda. First of all, I will briefly present the most important features of the communist planned economy.

3. Planned economy and the Stakhanovite movement

In the Soviet Union and after the World War II in the Eastern European,

socialist countries belonging to the Soviet sphere of interest a planned

economy system based on directive plans replaced systems built on market

conditions

18

. Its main characteristics were the following: «socialization of the means of production, planned economy, centrally commanded

redistribution, artificially determined investment and consumption ratios,

forced industrialization (...), the predominance of collectives in agriculture»

19

. Communist systems strove to outperform capitalist countries, the most

effective tool to achieve this in the field of economy was maintaining the

continuous competition, determining targets and exceeding those

20

. In socialist countries the plan - which could be an one-, three- or five-year

plan - was approved by the National Planning Office (Országos Tervhivatal) controlled by the communist party, this was approved by the

government and finally ratified by the parliament that only had a formal

function at the time

21

. In Hungary yearly planning was the real operational tool for the management of

the national economy, longer term plans rather served as statements of the

economic policy

22

. Typically the national economic plan embraced all aspects of economic

activity, including aggregated production indicators, the utilization of

products, labour force, investments, technological developments, foreign trade

indicators and price policies

23

. It is important to note that meeting the targets specified in the plan was

obligatory, this is why this system is referred to as “command economy, directive planning” in the literature

24

. As Stalin said: «our plans are not forecast-plans, not guess-work but directive plans»

25

.

Meeting and exceeding the targets was a continuous endeavour in the Eastern European socialist countries which was fuelled by the work competition campaigns. During the implementation of the first five-year plan (1929-1933) the Soviet Union faced serious difficulties due to the unrealistic targets. They tried to make the second five-year plan (1933-1937) more realistic, but Stalin expected the plan to be exceeded: to achieve this goal the existing work competition campaigns were further developed and the Stakhanovite movement emerged 26 . The movement starting in 1935 was based on the Aleksei Stakhanov’s performance: according to propaganda the miner from Donyeck accomplished 1457% of his daily plan and produced 102 tons of coal on 31 August 1935 27 . During the following weeks the Stakhanovite movement spread all over the country both in the light and heavy industry 28 . The significance of the movement is well illustrated by the fact that in the cover story of the 1 January 1936 issue of the Pravda, the daily newspaper and propaganda publication of the Soviet Communist Party, referred to the year ‘36 as “The Stakhanovite Year” 29 . To become a Stakhanovite, workers regularly had to produce more than required but being politically reliable was also an important prerequisite. In many cases, lacking clear guidelines, party secretaries or local trade union committee chairmen decided about the awards 30 . In numbers: by the beginning of 1937 nearly one quarter of the workers became Stakhanovites in the Soviet industry 31 .

In Hungary at the end of 1949 and national work offering movement started in the honor of Stalin’s 70th birthday which marked the emergence of the Hungarian Stakhanovite movement 32 . “Master of work” awards were given already from 1948 onwards 33 based on similar criteria as those of Stakhanovism. Stakhanovite awards could be received between 1950 and 1953 (in this period 115 thousand awards were distributed), which were later replaced by the «Excellent Worker» title, then this was stopped in 1956 34 . Based on recommendations of the National Committee of Trade Unions (SZOT) to receive master of work (later Stakhanovite) awards workers were not only expected to «exceed the targets for a longer period of time» or «have excellent results at the work competition campaigns» but political loyalty, that is «loyalty to the people’s democracy and the working people» was an important requirement also in Hungary 35 . Similarly to Aleksei Stakhanov, Hungarian Stakhanovites were selected and they often featured in propaganda publications that falsified real numbers to promote «the successes of the planned economy» and the importance of work competition campaigns 36 . The most well-known worker was Ignác Pióker, locksmith planer. According to propaganda he already completed the 1950 plan in May 1950, then the 1951 plan in October 1951 and the 1952 plan in March 1951. He was elected member of the parliament in 1953, the year when he was officially working to complete the plan of the year 1958. Pióker and the most significant Hungarian Stakhanovites (eg: Imre Muszka, lather, Zoltán Pozsonyi, bricklayer) regularly featured in the press and could often be seen and heard as propaganda elements of newsreels and radio broadcasts: by living «a life of virtue» in accordance with the «socialist concept of man» and with their political loyalty and strong work ethic they served as role models for the people during peace loan subscriptions and at work competition campaigns to make unpopular decisions more acceptable 37 . Stakhanovites serving the propaganda received higher wages and in Hungary they could get free bath tickets and holidays 38 . Stakhanovite propaganda was often built on lies: often several people worked for renowned Stakhanovites, thus they hardly worked for the results achieved 39 . It is important to note that the focus on quantity often lead to a decrease in quality and disproportions in the entire socialist block.

4. Top-class footballer masters of work

Following the 1948 London Olympic Games Mátyás Rákosi said:

«I would simply call the team of top-class Hungarian sportspeople, which excellently represents not only the Hungarian sport but also the Hungarian people’s democracy, the masters of work of democratic sport and if I were to distribute the awards of master of work, I would grant it to each one of them» 40 . With his statement that party leader implied that they intended to introduce the «master of work propaganda» also in the field of sport.

Probably as a result of this the sports daily, « Népsport » announced a call in the 11 November 1948 issue with the title: «What can we expect from a top-class athlete?» 41 . They formulated the question: what does the flattering description by Mátyás Rákosi, «the masters of work of sport» refer to? «Top-class sportspeople might have other duties besides victory and the sport results» - came the assumption, then further questions were asked:

is it enough if somebody throws far, scores a goal or swims fast - and can they do whatever they want in their private lives? Can they behave the way they want to? Do they work only if they want to and if they choose not to, then they don’t? Are those who achieve great results in sport allowed to do more or less? Do they deserve extra support or not? Should they work more than others or not? (...) Do the champions of our people’s democracy have any political duties? (...) How should top-class sportspeople behave on the pitch, at their workplace, at home? Does excellence in sport mean more rights or more commitments 42 ?

Until the submission deadline on 17 November, 212 applications arrived according to «Népsport» 43 . The applications of the first three award winners 44 - who received 500, 300 and 100 forints as prize - were published on 10 December, then until 21 December further applications were published in almost every issue. Based on the applications received «almost all of them emphasized that top-class sportspeople cannot be idle parasites of the society». Moreover «there are many who wish that more and more top-class sportspeople were masters of work as well» and «there is none who would not condemn the type of the work-shy star». One of the readers, a trade employee explains that

a top-class sportsperson has the duty to work besides their sport activity. At least as much as an average worker because without this they would not have the moral justification to be called top-class sportsperson in spite of their outstanding achievements in the field of sport. They should be modest, politically educated and informed and should have extensive knowledge about the economic situation of the country 45 .

According the the application of an academician while before the «liberation»

during the rotten capitalism a small number of top-class sportspeople bred to professional sport formed a separate cast, now the situation is different. The possibility of sports has opened up for working people. It is the task of the people to fill the concept of sport with noble content and top-class sportspeople can contribute to this 46 .

These ideas were summed up by the editor-in-chief of the newspaper, László Marschall in his lead article titled «Top-class athlete=master of work» in the 29 March 1949 issue claiming that one of the main tasks of top-class

athletes is to “lead the fight to create the new socialist prototype of man.”

The communist party regularly used popular footballers for ideological purposes, among others to promote the success of the planned economy, one of the main pillars of communist ideology and to demonstrate the types of behaviour expected from workers. This is well illustrated by the portrayal of Jószef Zakariás, the midfielder of the Golden Team, in «Népsport». According to the article titled the «Top-class athlete who is not just a hero of Sundays but also of workdays», even in his childhood the principal of the civic school in Budafok «failed to persuade» the excellent player of the national team to play in the «’rightwing BIK’, he was only willing to play» in the «workers association». The reader is also told that, after the «liberation», Zakariás was among the first to volunteer to clean up the ruins and start local sports life”, in his current team, the MATEOSZ «he is among the first to arrive at trainings and among the last to leave.» As it turns out, the player

does not use body tricks, he is not playing for the spectators but for the community, his team. His main virtue is that he always chooses the simplest solution. (...) He also excels in production because he always bears in mind that only those can be top-class sportspeople who stand their ground at work too.

- emphasizes the author adding that «as a recognition of his work as a clerk at the Freight Transport NV he received

300 forints reward. He is appreciated at his workplace, he is not only a good

football player but an excellent worker too. (...) He is hard-working and

self-sacrificing, always serving his community, his career has been marked by

successes. However Zakariás is unsatisfied. ’I would like to improve’» – said the midfielder who also shared: at the moment he is only a candidate for

membership but he would like to become a member of the MDP as soon as possible.

The writer of the portrait concludes: «Zakariás is a top sportsman. His name is associated with great successes in Hungarian

sport. However this affects his character differently than the stars of earlier

times. One who is not only good at sport but excels at work as well has proven

that for them sport is not an excuse, not a right to work less»

47

.

In the portrait the journalist adds that Zakariás is «married and has a three-month old son»

and he is keen on training young footballers, referring to his familiy-centered,

virtuous and conscious lifestyle. Work ethic, loyalty to the party and a

virtuous behaviour all appear in the description.

It is important to point out the paradox of the communist system: in Hungary athletes officially had an amateur status, they received their salary for their work at a state-owned workplace unrelated to sport 48 . However in most cases top-class sportspeople and top-class footballers - especially in teams strongly supported by the regime 49 - did not have to do real work besides sport. Károly Sándor, right winger of the team Bp. Bástya falling under the authority of the State Protection, “worked” in the TEMAFORG warehouse of the Ministry of Light Industry in the beginning of the 50s but he did not have to go to work because if he did, all the workers asked the star footballer about the games and nobody worked. As he later said: «They asked me not to go to work because if I do twenty people will not work, so they will rather allow me to stay away from work» 50 .” Besides their salary footballers received further calorie benefits 51 or a food package to ensure proper nutrition and they got a bonus on the points they collected at championships. In this way they were able to earn a salary that was multiple times higher than that of average Hungarian wages 52 . The most privileged football players received a further significant benefit, they were allowed to smuggle quality goods in short supply in Hungary – e.g.: nylon stockings, wrist watches - which they could then sell in Hungary 53 .

So no matter how much the «Népsport» was trying to propagate that László Budai II, member of the national football team «goes to work happily to the Hutter factory every morning, which belongs to him too» 54 in most of the cases these were false or exaggerated statements - moreover if footballers had been really forced to work, it would have caused their performance to significantly drop and as the successes of the national football team were of great importance to the communist party they could not have allowed this to happen.

The portrayal of the best football players and athletes as excellent workers was not unique to Hungary within the socialist block. When as part of the competition with western societies the Soviet political leadership announced at the beginning of the 30s that also in the field of sports «all world records should belong to the Soviet Union», paralelly to the Stakhanovite movement a new cult emerged where top athletes broke «production records» in their own field 55 . Several athletes became celebrated stars in the Soviet press, spreading the glory of the «working people» 56 . In the countries that came under Soviet influence after 1945 top-class sportspeople were compared to or even identified with masters of work. This is well illustrated by an example similar to the Hungarian situation: Iosif Sarbu, sporting shooter and first Olympic champion of Romania was described by Romanian newspapers not only as an outstanding sportsman but also as an excellent clerk and student 57 .

5. The match of the century

Fig 1: «We will bring the 1953 plan to victory» underneath: «The Electricity Company has completed the plan» - on both sides portraits of Hungarian footballer winning the match in England the day before, in «Népszava» (People’s voice), 26 November 1953.

The communist party did not only use the players for political purposes but also the victories of the team: to demonstrate the success of the society and the country or in certain cases to promote the planned economy.

Offerings and work competition campaigns were often held alongside with sports events and matches. Other times a political event was introduced to the world of sport. Such an event was the 70 th birthday of Stalin in December 1949 which became the central theme of the sports newspaper during the preceding days and weeks 58 . The «Népsport» reported about the mass offerings of sportspeople on the front page, for example that footballers of the first class «Csepel team decided to do a night shift in the factory after their regular day shift and as a kind of» general reserve « they would help wherever they are needed» 59 . After the “Stalin-shift” on the birthday of the “generalissimus” the newspaper continued to regularly report about the «Korean shift» during the Korean war where athletes strove to achieve great results to support «Korean people fighting for their independence» 60 .

In several cases outstanding sports successes got such a press coverage that - at least according to the propaganda - could encourage people to make offerings 61 . An example of this was the Helsinki Olympic Games 62 where Hungarian sportspeople finished third on the medal table after the USA and the Soviet Union with 16 gold medals. As next I will present the economic propaganda related to the probably greatest success of the history of Hungarian football, Hungary’s 3-6 victory against England on 25 November 1953.

The national team of England had not been defeated on home ground by a team coming from outside of the British Isles for 90 years, so the Hungarian public was looking for the guest of appearance of the Olympic champion Golden Team in London with great excitement and was expecting a victory under any circumstances. The press also contributed to public mood and for the political leadership the victory provided a great opportunity to demonstrate the country’s political, social and economic supremacy over England, a leading state of the West. Already during the days before the match «Népsport» published articles about coal miners in Balinka offering to increase production 63 . In honour of the great victory exceeding all expectations 64 the first offerings were made already in the issue of the following day, 26 November. József Igaz (in English: József True ), Stakhanovite foreman of the Hungarian Cotton announced a «6:3 shift» on 2 December, a week after the victory. He stated: «During this shift we want to exceed our performance so far just like our footballers exceeded all expectations in London. We encourage all the sport-loving people of the country to join us. In factories, state farms, collective farms, let’s show them how much Hungarian workers value their sons’ victory». Afterwards the 27 November issue was flooded by reports about the performance enhancing effect of the victory. In the MÁVAG factory in the capital «work went more smoothly», during the match «twice as many workers were in the factory as on other workdays. Many of those working in the morning shift stayed in the factory to listen to the broadcast of the match» on the radio. According to the article in the excited atmosphere of the match «the metal-worker brigade of the locomotive factory performed 210% by the end of the shift. János Berze, body ironer reached 291 percent by 10 o’clock in the evening. The workshop of the locomotive factory had an average result of 120%, whereas it rarely had results reaching 100% before». Similar news came from the Goldberger Textile Factory and the 6. site of the Budapest Underground 65 . After a while stories published in the newspaper became more and more colorful and fictional: according to the article «600 wagons of coal for 6 goals» the Stakhanovite mining front master in Tatabánya promised «100 wagons» of coal above the target 66 .

The «Népsport» published an on-the-spot news report about the 6:3 shift held on 2 December. The article gave a detailed report: the first to arrive at the factory «at 6 in the morning» was József Igaz, who announced the 6:3 shift. His brigade «prepared 1050 pieces of textile above the target within 8 hours», which - according to the newspaper - «would be enough for nearly 700 football jerseys» 67 . The «Népsport» reported about the nationwide success of the shift on 4 December and on 10 December it reviewed factories where the yearly plan was completed during the 6:3 shift. It is interesting to note that the sports newspaper did not only speak about reaching and exceeding targets but they also took into consideration who were not able to participate in production yet due to their age but constituted the future work force:

Students, who do not produce yet, also want to celebrate the great victory of

Hungarian sport with an offering. Ilona Bicsics, DISZ secretary was the first

among the students of the Mester street secondary school of economics to offer

to improve her study results by 10%. Following her example several other

students of her school made similar offerings

68

.

Another noteworthy detail is that economic propaganda was built into the language of the newspaper and special phrases were coined those days like: «The Puskás-brigade from London outperformed the plan» 69 .

The victories were not only used to encourage workers but also to demonstrate the unquestionability and supremacy of the socialist planned economy system as opposed to western capitalism. On their way back home the national team played in the French town of Malakoff where according to the newspaper the communist mayor of the town stated: now you can finally see with your own eyes “what results people can achieve in a people’s democracy where sports opportunities are also ensured”, he added that local opportunities «could not even be compared to those in Hungary». The writer of the article also remarked condescendingly that:

As we look around in the sports hall, we can see shabby sports equipment and basketball boards set aside. We can see pictures depicting sports events on the walls. We can see that the room is furnished poorly but with affection. The ground is stony, ragged and bumpy. The splendor of the Champs Elysées has not reached this place. This is the home of worker athletes 70 .

The press did not report about the completion of the large-scale offering of the Igaz brigade which was supposed to last until the “revenge” against England in May 1954 that in the end brought a 7-1 Hungarian victory, however the 1954 World Cup provided new opportunity for the production propaganda through football. The articles of the «Népsport» and other papers reflected the expectations of the party leadership and the majority of the society: only a gold medal was acceptable at the Cup. Starting from the end of June the press regularly reported about organising «World Cup shifts» 71 , thus «motivating» and «showing respect» towards the national team marching towards the final. Surprisingly however the team lost the final against West-Germany 3-2, which caused such disappointment that people took to the the streets of Budapest where they demonstrated and caused violent disturbances 72 . After these events the propaganda function of football significantly diminished and the Administrative Department of the Party emphasized in the report:

The People’s Sport, the Free People and other papers and the radio overly enhanced the

interest of the public in the World Cup. Organizing the »World Cup shift« in the factories was incorrect and it backfired after the defeat. The Free

People and other papers gave football too much attention, in many cases

important issues of economy, production and foreign affairs were sidelined. The

great disappointment and depression after the defeat resulted from an overly

intensified public mood and expectation...

73

László Feleki, chief editor of «Népsport» (People’s Sport)- who probably followed political commands - was made a scapegoat and

was removed from his position and the regime used players and football matches

for political or economic propaganda to a much lesser degree.

Additional information to the events: József Zakariás, the master of work-top footballer portrayed in detail previously - also became a scapegoat after the lost final. Decades later Zoltán Czibor, former team mate who later signed to Barcelona anonymously but unmistakably referred to his room mate Zakariás when he said: the player got back to their hotel room in Solothurn in the morning after having spent the night with one of the hotel’s maids. «At six o’clock in the morning he staggered home, maybe even his legs were shaking... (...) “and I had to win the World Cup with this man!» 74 . It is a fact that after the lost final in Bern it was only József Zakariás out of the classical eleven of the Golden Team who could never play again in the Hungarian national team 75 . Whether the story is true or not, the question arises to what extent the ideal of workers «making offerings» and «performing 250-300%» after hearing about the 6-3 victory and «tirelessly building socialism» corresponded to reality, real work performance and lifestyle if a top sportsman of the socialist system could receive such charges.

6. Football propaganda and the first five-year plan

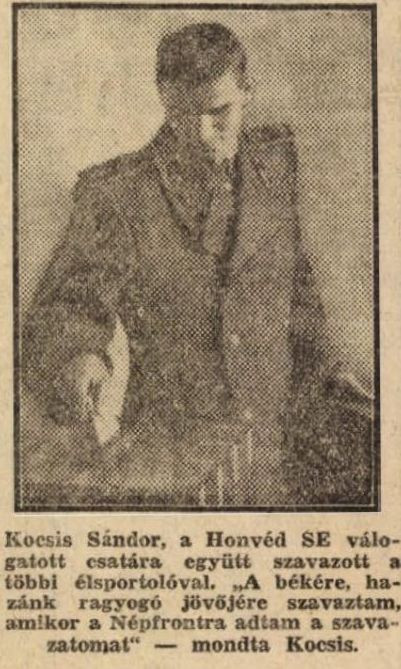

Fig 2: «Sándor Kocsis the forward of the Honvéd SE and the national team has voted together with the other top-class sportsmen. ’I have voted for the peace, the bright future of our country when I have given my vote to the Népfront’ – said Kocsis», in «Népsport», 24 October 1950.

Footballers were used in various propaganda campaigns related to the implementation of the planned economy and the first five-year plan. Among these were the matters of plan and peace loan subscriptions.

During the Rákosi era investments - mainly serving military purposes - significantly rose, the officially voluntary but in reality obligatory acquisition of state bonds was meant to cover these costs. Between 1949 and 1954 peace loan subscription campaigns were held six times altogether, in the total value of 5.6 billion forints 76 .

During the campaigns the papers were full of appeals for bond subscription and footballers were expected to participate. During the first loan subscription in 1949 besides the offerings of the Olympic champion fencers the newspaper of the communist party also reported that Zoltán Czibor, only 20 years old at the time, «showed a good example» by subscribing 3 three months of salary 77 . During the campaign the «Népsport» - presumably to influence female readers - even presented the opinion of the footballers’ wives through the two brothers Imre Kovács II and József Kovács, members of MTK and the national team: «It was not difficult to explain it to my wife» - revealed Imre.

She said that she used to save money before but she could never save enough to

buy something substantial. She always opened the coin box too early or took the

money hidden under the shirts. ’Now the money will be in a safe place at least’ - she said – ’as our lives and the future of our children are now safe too’. ’My wife already knew about it’ - said József - She wanted to explain to me why the loan subscription is important!

78

Similar enthusiastic accounts and colorful stories were common during the campaigns 79 and often created a kind of competition among footballers and the teams, always making sure that the higher class a footballer was, the more he subscribed. Thus when the propaganda reported about the footballers of Honvéd, the biggest stars, Ferenc Puskás and Sándor Kocsis subscribed 5000 and 4000, while the less popular, but still well-known and excellent footballers László Budai II and Gyula Lóránt subscribed 3000 80 . The articles also contained the percentages mentioned before. So for example in the case of Lajos Faragó, the reserve goalkeeper of Honvéd, the article highlighted that he subscribed «250% of his salary» 81 . Besides the great stars the propaganda also used «ordinary people» through football: an example for this is when young barefoot peasants playing with shabby footballs somewhere in a faraway corner of Hungary are reading the political news about the subscriptions with great satisfaction thinking: there will be enough money also for them to buy a new ball 82 .

In Hungary the main investment of the first five-year plan - after several delays - the building of the People’s Stadium (Népstadion) was completed in 1953. Jenő Tapolczai, vice president of the National Committee of Physical Education and Sport (OTSB) made the following comment about the investment whose costs kept rising and finally amounted to more than 100 million forints: at the same time «students at the College of Physical Education live in a run-down rathole that leaks every time it rains» 83 . Nevertheless, due to the increased interest, the national football team really needed a stadium with a capacity of nearly 100 thousand people 84 , and according to plans, this would have been the main venue of the 1960 Olympic Games as well. The grandiose building was built specifically for representative purposes that was intended to be «the symbol of peace, monumentality and social equality» showing off «how developed» the socialist economy was 85 . According to propaganda, brigades of top footballers also contributed to the construction with voluntary work. A 14-member brigade of the athletes of Honvéd - among them Ferenc Puskás and Sándor Kocsis - «did work in the value of 404 forints within 2 hours: they removed 200 metric centner of concrete building elements, 80 metric centner of iron and they prepared 24 cubic meter gravel for concreting» 86 . According to the paper, the stars of Dózsa excelled at work too: Ferenc Szusza and Ferenc Deák «worked at the gravel sifter», Béla Egresi, Mihály Tóth and István Virágh «shoveled the gravel». The author of the article compared their work performance to their achievements on the football pitch: «as on the pitch, Egresi turned out to be the fastest. Virágh and Tóth stood out with their diligence and Szusza with his calmness» 87 . At the inauguration the People’s Stadium Gyula Hegyi, president of the OTSB said: athletes contributed to the construction with more than 150 thousand hours of voluntary work 88 . According to the propaganda, the brigades of various sport clubs regularly participated in the building works of sport facilities in their own settlements: for example in Pécs, Debrecen, Sopron and Szeged 89 .

It is noteworthy that top footballers were also used for propaganda purposes related to the elections. The operation of the planned economy was guaranteed by the communist party and to gain formal legitimation to lead the country, they needed to win the parliamentary and the local elections. During the elections the most famous footballers regularly encouraged people to vote for the communists on the pages of «Népsport» 90 . Gyula Grosics, popular goalkeeper of the Honvéd and the Golden Team stated in the sports newspaper during the local elections of 1950: «Today all athletes have to know what it means to vote for the Népfront (Popular Front): an easy livelihood, relaxed sporting opportunities, a bright future and the successful completion of the five-year plan» 91 . Of course there was no stake: in the one-party system there were no real elections, only candidates of the communist party could appear on the ballot-papers.

7. Summary

The propaganda representation of top footballers as masters of work served various purposes: firstly they demonstrated that in the «society of working people» even celebrated, famous footballers worked like ordinary people - that was not the case in reality. Secondly: with the help of sport idols and successful role models they tried to encourage hard work, a virtuous lifestyle, social responsibility and party loyalty. With all these they tried to achieve the targets of the planned economy - besides promoting important socialist ideas. The calls and readers’ letters published in the sports newspaper were intended to create the impression that the population expected or even demanded top footballers to behave accordingly and «become a socialist man».

The biggest football victories, like the 6:3 victory of the national team against England in 1953 were also used for propaganda purposes, besides the social and political implications. Upon hearing about the victory, according to the propaganda, a Stakhanovite reader initiated a 6:3 shift in the following issue of the «Népsport» to encourage workers to honor the result of the team. In the course of the following days there were several propaganda reports that during the shift - and already during the match, listening to the events on the radio - workers became so motivated that they significantly exceeded their daily targets. During the Rákosi era newspapers often dealt with the partial results of the yearly plan and urged faster, more efficient production, the propaganda related to the 6:3 victory is an example of this. A similar attempt was made during the much awaited 1954 World Cup: several factories organized «World Cup shifts». According to the propaganda, workers made work offerings in the hope of winning the Cup. After the lost final, these campaigns suddenly stopped.

Top footballers were also used to promote unpopular social measures: for example the plan and peace loans, when according to the press footballers voluntarily and enthusiastically offered one or even more months salary for the benefit of the country, «building socialism» and the communist ideology. Players also had to participate in the election campaign of the communist party and several articles reported about Ferenc Puskás and other football players doing manual labour at the construction of the People’s Stadium, the first main investment of the five-year plan.

Though it cannot be proved with certainty in every case, but based on knowledge about the Rákosi system and communist systems in general, facts about the situation of the Hungarian press at the time and information from interviews made with players subsequently, we can state that both the “master of work portrayal” of top athletes and the 6:3 shift and other labour offerings were based on exaggerations and lies and they only existed in the “reality” of the propaganda. It is hard to imagine that ordinary workers, who were in fact happy about the victories, would have expressed their joy by doubling production. The production results of famous Stakhanovites can also be questioned considering the nature of the system. Presumably the main purpose of these articles was to present and confirm the «stability and success» of the planned economy system, the political and social system of socialism. There was an educational purpose too: after the 6:3 victory they tried to encourage learners, «workers of the future» to perform better at school. Since during this period papers often published calls for work offerings and the «Szabad Nép» (in English: Free People) regularly discussed production targets, what is especially interesting is that they tried to present this through football as well - due to its popularity and presumed motivating force. We can find similar patterns related to the election campaigns and the peace loan subscriptions, with the difference that these offerings and statements praising the Party were in fact made during the oppression of the period - in most cases according to recollections presumably under duress 92 , sometimes maybe based on personal conviction. As in the press of the Rákosi era only opinions supporting and praising the system could

be published, it is difficult to draw conclusions. In any case, it is peculiar that the regime tried to used footballers and their victories even in the field of economic propaganda with such intensity.

1 6:3 shift , in « Népsport » (People’s Sport), 26 November 1953

2 To demonstrate this, I use the example of the England-Hungary match on 25 November 1953 that was of great significance in the period.

3 Cfr. L. Feleki, Hungary-England 6:3 (4:2) , in «Népsport», 26 November 1953, article of «Népsport» following the 6:3 victory: «The overwhelming and practically smashing victory of our footballers in the homeland of football can be rightly compared to the Olympic Games and other unforgettable successes of Hungarian football, it is a living proof of the talent and strength of our people and of the supremacy of the socialist system that enables people’s talents to unfold».

4 The economic aspects are very important as socialist systems base their supremacy over capitalist systems mainly on the superiority of the economy and production. Therefore the socialist economy can be viewed as one of corner stones of the system. J. Kornai, The Socialist System. The Political Economy of Communism , Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1992, pp. 82-83.

5 Until 1948 Hungarian Communist Party, after 1948 Hungarian Working People’s Party.

6 The era of the Rákosi system lasted from 1948 to 1956. After Stalin’s death, during the first prime ministership of Imre Nagy, starting from the summer of 1953 the politics of the dictatorship eased considerably due to pressures from Moscow, though Rákosi and his supporters soon reinforced their positions and the party leadership was trying to return to its former politics. It was the revolution of 23 October 1956 that put an end to Rákosi’s system. It is important to note in connection with the present study that after 1956 in the – also communist – system of János Kádár the direct use of sport and football for political purposes (e.g.: in the propaganda) was much less typical.

7 It is a typical phenomenon in Europe that, during its evolution, football became much more popular than other sports. See e.g. in the Soviet Union: R. Edelman, Serious Fun. A History of Spectator Sports in the U.S.S.R. , Oxford UP, New York-Oxford, 1993, pp. 160-165. The reason for this is that the interest develops through the supporters’ sense of identity that is created in the competition of clubs. Thus individual sports cannot have the same effect (except for world sports events e.g.: Olympic Games where the team represents the given nation). Football stands out among team sports as well: it is cheap, easy to follow, it is available to the poor as well. Physical space also play an important role: at a football game 80-100 thousand fans can be present which is usually not feasible in the case of handball or basketball.

8 Looking at the number of spectators of first class championships we can see a steady increase in interest. While before 1945 the “top year” was 1926/1927 with 7443 spectators, between 1948/49 and 1955 the numbers changed as follows: 6676, 7341, 5642, 8596, 10058, 11015, 13365, 17179, [https://www.magyarfutball.hu/hu/nezoszamok] (last access 28 december 2020). In the 1955 season there were already 18(!) matches that were watched by at least 50 thousand people, [https://www.magyarfutball.hu/hu/merkozesek/bajnoki_merkozesek/nb_i/1955/nezoszamok], (28 december 2020) and it cannot only be explained by the fact that before the completion of the People’s Stadium ( Népstadion ) in 1953 there would not even have been a possibility for this. The increase in the number of spectators after the World War II was not only typical in Hungary, it was also noticeable in the capitalist England in the more relaxed atmosphere after the horrors of the war, but it was then that it acquired wider mass base and became part of popular culture in the communist Soviet Union as well. J. Walwin, Lesiure and Society 1830-1950 , London, Longmans, 1978, pp. 148-151; Edelman, Op. cit., p. 92.

9 B. Borsi-Kálmán, Az Aranycsapat és a kapitánya , Budapest, Kortárs, 2008, pp. 41-42.

10 According to the communist system, the traditional club structure originated in the “fascist” system before ‘45.

11 E.g.: FTC supporters were celebrating the leader of the Hungarian catholic church, József Mindszenty while they were referring to Pál Mindszenti substitute goalkeeper at the games. T. Dénes, M. Sándor, BAJ-NOK-CSA-PAT! – A magyar labdarúgás tizennégy bajnok klubjának története , Budapest, Déró Szerk. Kft., 2012, p. 45.

12 Based on Soviet example sport clubs all over the country were taken over by armed services, ministries and trade unions. The teams of armed services - according to the militant worldview of the Stalinist regimes - got the most support and the best players. (Defence: Budapesti Honvéd [formerly Kispesti AC], home affairs, police: Budapesti Dózsa [formerly: Újpesti Torna Egylet], state security: Budapesti Bástya [formerly: Magyar Testgyakorlók Köre - MTK]. While the Ferencvárosi Torna Club (FTC), labelled as reactionary and adversary, became the team of food industry, a disadvantaged sector in the country of iron and steel, under the name of Bp. Kinizsi. Its best footballers were sent to the Honvéd and Dózsa.

13 J. Riordan, The Impact of Communism on Sport , in «Historical Social Research», Vol. 32, No. 1, (2007), pp. 110-114.

14 Defence is a very important aspect for example relative to mass sport, in 1949 the Prepared for Work and Fight movement came into being where people from cities and the countryside could compete with each other in different sports to maintain their physical fitness. Its Soviet predecessor was: Prepared for Work and Defence, in Russian: Gotov k trudu i oborone , cfr. Riordan, Op. cit., p. 112.

15 Farkas was informally the omnipotent leader of the Bp. Honvéd, the show team of the period.

16 Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár (MNL), M-KS (documents of Hungarian Working People’s Party) 276th fond (documents of central organs), 67th group (secretarial documents of Mihály Farkas), 209th guard unit, 1948.

17 R. Szabó, Volt egyszer egy mérkőzés , in «História», Vol. 25, No. 8-9, (2003), pp. 33-34.

18 For a detailed description of the planned economy cfr. Kormai, Op. cit.

19 J. Gagyi, Fejezetek Románia huszadik századi társadalomtörténetéhez , Târgu Mureș, Mentor Kiadó, 2009, p. 124.

20 Ibidem .

21 Kornai, Op. cit ., p. 111.

22 Ibidem .

23 Ivi , pp. 111-113.

24 Ivi , p. 114.

25 Ivi , p. 113.

26 S. Horváth, Gy. Majtényi, E. Zs. Tóth, Élmunkások és sztahanovisták , in «História», Vol 20, No. 8, (1998), p. 29-32. For more details about the history of the Stakhanovite movement cfr. L. H. Siegelbaum, The Making of Stakhanovites, 1935-36 , in «Russian History», Vol. 13, No. 2-3, (1986), pp. 259-292; R. W. Davies, O. Khlevnyuk, Stakhanovism and the Soviet Economy , in «Europe-Asia Studies», Vol 54, No. 6, (2002), pp. 867-903.

27 Horváth, Majtényi, Zs. Tóth, Op. cit.

28 Davies, Khlevnyuk, Op. cit., p. 879.

29 Ivi, p. 880. The authors point out that in 1937 purges began in the Soviet industry that overshadowed the real effect of Stakhanovism. Therefore 1936 is the most significant year for the study of the performance boosting effect of the movement. Altogether Stkhanovism did not bring about significant performance increase in the Soviet industry. Though some developments occurred as a result, it also lead to disproportions in production and a huge amount of surplus cfr. Ivi , pp. 882-898.

30 Siegelbaum, Op. cit., , pp. 277-278.

31 Ivi , p. 263.

32 See e.g. the issues 1-31 December 1949 of the «Szabad Nép» (Free People).

33 The term «master of work» and its use for propaganda purposes became common in propaganda newspapers from 1948 March, in the «Szabad Nép»(Free People), «Népszava» («People’s Voice») and «Magyar Nemzet» («Hungarian Nation»).

34 Horváth, Majtényi, Tóth, Op. cit., p. 30.

35 Proposal for a Final Statue for the Award of Master of Work , in MNL, M-KS 276th fond 55th group (Organizing Committee of Hungarian Working People’s Party) 77th guard unit, 4 July 1949.

36 E.g.: I. Pióker, «How can I exceed my target?», in «Szabad Nép», 31 December 1950. Or: Ignác Pióker completed his five-year plan, in Magyar Filmhíradók Online, December 1950, [ https://filmhiradokonline.hu/watch.php?id=10981 ], (1 July 2020).

37 Horváth, Majtényi, Tóth, Op. cit. The education of the new generation of Stakhanovite workers also appeared in the propaganda through them, the “masters” taking care of the young.

38 Horváth, Majtényi, Tóth, Op. cit.

39 Interestingly János Göröcs (1939-2020), legendary footballer of the history of Hungarian football after the Golden Team served as a miller apprentice with Ignác Pióker in his youth. As he said: he only saw the famous Stakhanovite at the machines in the mornings, then he disappeared for the whole day. A.Ch. Gáll, Nekünk mindig pechünk volt – interjú Göröcs Jánossa, az Újpest legendájával, in «Origo», 31 May 2011, [https://www.origo.hu/sport/futball/20110531-interju-gorocs-janossal-az-ujpest-legendajaval.html], (1 July 2020).

40 The masters of work of democratic sport…, in «Népsport», 27 August 1948.

41 Such calls in the «Népsport» officially represented the readers’ opinions, but in reality only opinions that were in alignment with the communist propaganda were published. Therefore probably only selected writings were published or they were written by the paper’s pen-pushers. The similarity in the wording of the writings implies the latter.

42 What can we expect from a top-class athlete? , in «Népsport», 11 November 1948.

43 212 applications arrived according for What can we expect from a top-class athlete? call, ivi , 21 November 1948.

44 The first prize went to a body ironer, the second to a miner from Tatabánya, the third was given to Ilonka Novák, who became an Olympic champion swimmer later. Cfr. The result of What can we expect from a top-class athlete? call, ivi , 10 December 1948.

45 What the public expects from a top-class athlete?, ivi , 16 December 1948.

46 A top-class athlete should be an honest worker! , ivi , 19 December 1948.

47 A top-class athlete who is not just a hero of Sundays but also of workdays , ivi , 16 February 1950

48 It was based on the idea that professionalism in sport characteristic of capitalist systems was incompatible, immoral and contrary to the spirit of sport. They rejected the “star cult” and according to the communist ideology of equality it was inconceivable for football players of state-owned teams to get a significantly higher salary than ordinary people.

49 The footballers of the Bp. Honvéd (the team of the army), the Bp. Bástya (State Protection) and the Budapest Dózsa (Ministry of the Interior) officially worked in the military, state security or police service.

50 R. Szabó, A jobbszélső – interjú Sándor Károllyal , jn «História», Vol. 25, No. 8-9, (2003), p. 49.

51 I. Kamondi, Labdarúgó krónika-Nemzeti bajnokság I. osztály , Pécsi Dózsa-PMSC 1955-1984 , Pécs, East Bt., 1994, p. 8.

52 Szabó, Op. cit. , p. 49.

53 This was a kind of compensation as the communist leadership knew: in Western Europe top footballers could have earned considerably more than the Hungarian salaries. For more details about smuggling see B. Borsi-Kálmán, Az Aranycsapat és ami utána következik , Budapest, Kortárs, 2019, pp. 23-24. Signing to the West was prohibited, still many footballers attempted it. The regime put an end to this with a show trial in 1951. The State Protection Authority trapped Sándor Szűcs, a player of the national team by organizing his defection. Afterwards the football player was sentenced to death and executed which served as a deterrent for those planning similar attempts. N. Tabi, A futballistaper. Szűcs Sándor válogatott labdarúgó kivégzésének története , in «Rubicon történelmi folyóirat», Vol. 25, No. 7, (2014), p. 28-33.

54 It’s easy to be a sports mom today – Why do Aunt Kabos, Aunt Papp, Aunt Király vote for the People’s Front?, in «Népsport», 8 May 1949.

55 B. Keys, Soviet Sport and Transnational Mass Culture in the 1930s , in «Journal of Contemporary History», Vol. 38, No. 3, (2003), p. 420.

56 Edelman, Op. cit., p. 76. For example the runner brothers Seraphim and Georgy Znamensky and the pole-vaulting Nikolai Ozolin.

57 C. Pompiliu-Nicolae, V. Maier, Sport and Physical Education in Communist Factories: from the Soviet Union to Romania , in « Romanian Journal of History and International Studies », Vol. 2, No. 2, (2015), p. 221.

58 See e.g. «Népsport», 11 and 15 December 1949 issues.

59 A day before the Stalin-shift – Another mass offerings of Hungarian athletes by December 21st , in «Népsport», 20 December 1949.

60 E.g. Ivi , 15 July 1952

61 Political newspapers were full of such articles and appeals encouraging extra work all round the year, unrelated to sports as well. (E.g. «Szabad Nép», 30 November 1953; «Szabad Nép», 1 November 1952; «Szabad Nép», 1 November 1950, «Szabad Nép», 1 July 1952).

62 E.g. «Népsport», 14 August 1952.

63 L. Feleki, Enthusiastic home telegraph messages greeted our footballers at their London accommodations , ivi , 24 November 1953.

64 László Feleki, the chief editor of «Népsport», which was to a great extent responsible for enhancing the mood, mentioned amidst the high expectations before the match a bit pretentiously: «Sport mates, would an one goal victory not be enough?». Cit from L. Feleki, Enthusiastic home telegraph messages greeted our footballers at their London accommodations , ivi , 24 November 1953.

65 The work went harder , ivi , 27 November 1953.

66 Ivi , 29 November 1953.

67 6:3 shift – 1050 meters of textile beyond plan , ivi , 3 December 1953.

68 Ivi , 29 November 1953.

69 «Népszava», 26 November 1953.

70 L. Feleki, Our footballers are among French working athletes , in «Népsport», 30 November 1953.

71 E.g. in Tatabánya ( “Szabad Nép» , 30 June 1954) or in Stalin City ( Sztálinváros ) ( “Szabad Nép» , 2 July 1954).

72 N. Tabi, Volt egyszer egy Futbólia – A labdarúgás legitimációs szerepe a Rákosi-korszakban , thesis in manuscript, Corvinus University of Budapest, Political Science MA, 2016, pp. 63-70.

73 MNL, M-KS 276th 54th fond (Secretariat of the Hungarian Working People’s Party), 334th guard unit, 1954.

74 M. Bocsák, Kocsis és Czibor , Budapest, Sport, 1983, p. 63-65. It turns out that not only Zakariás but another five players «were out» that night.

75 Borsi-Kálmán, Op. cit. , pp. 102-105.

76 T. Valuch, Magyar hétköznapok. Fejezetek a mindennapi élet történetéből Magyarországon a második világháborútól az ezredfordulóig , Napvilág, Budapest, 2013, pp. 32-33. Though it was called a loan, the majority of citizens never got back the real value of the amount they paid. The expected payment was one month, those who refused to pay could expect severe retaliation. Thus it served as a kind of «hidden tax». Cfr. M. Deák, P. Kiss, Jegyezz békekölcsönt! Egy munkás kálváriája az ötvenes években, in «Archivnet» , Vol. 5, No. 3, (2005), [ https://archivnet.hu/hetkoznapok/jegyezz_bekekolcsont.html ], (5 August 2020).

77 This is how our Olympic champions, world champions and the masses of athletes subscribe the plan loan , in «Szabad Nép», 30 September 1949.

78 What do the wives say , in «Népsport», 2 October 1949.

79 See e.g.: the subsription of the players of Dózsa, ( ivi , 26 September 1952) the players of Dorog ( ivi, 4 October 1949), the players of Csepel ( ivi , 30 September 1952).

80 It was emphasized that 20 footballers subscribed altogether 51 thousand forints, cfr. Ivi , 26 September 1952.

81 Twenty footballers of Bp. Honvéd: 51 thousand forints, ivi , 26 September 1952.

82 Football ball, tennis rocket and ping pong ball – topics that affect the five-year plan one by one, ivi , 4 October 1949.

83 MNL, M-KS 276th fond 96th group (Administrative Department of the Hungarian Working People’s Party), 3rd guard unit, nn.

84 From that point on several first class teams from Budapest played their championship games here, often in front of 60-80 thousand supporters.

85 Besides the People’s Stadium in Budapest, the teams of Bástya, Vasas, BVSC and REAC also got a new or renovated stadium, while in the countryside teams could play in more modern facilities: e.g., in Eger, Debrecen, Sopron and Pécs.

86 The participation of athletes in the construction of sports facilities has expanded into a country-wide movement , in «Népsport», 15 April 1951

87 Four Dózsa brigades for the People’s Stadium , ivi , 15 April 1951.

88 The new pride of our five-year plan, the People’s Stadium is inaugurated , in «Szabad Nép» , 21 August 1953.

89 The participation of athletes in the construction of sports facilities has expanded into a country-wide movement , in «Népsport», 15 April 1951.

90 E.g.: during the parliamentary elections: «Once again: why? Why do Imre Németh, Ferenc Rudas, Gizi Farkas, József Nagy, Aunt Király, Ibolya Csák, Béla Szekeres [navvy from Kiskunfélegyháza] and the huge army of sports vote for the People’s Front today». Cit. from We are leading in sport, we will finish first at the ballot boksz as well! , ivi , 15 May 1949) and «Károly Sándor and his wife are going to vote» cit. from P. Fekete, Can I write some welcome lines on the back cover? , ivi , 17 May 1949).

91 This is how the top-class sportsmen of Honvéd voted , ivi , 24 October 1950.

92 E.g.: at the 1952 world peace congress in Vienna Ferenc Puskás also had to give a speech as a member of the Hungarian delegation, however it is known that the Hungarian footballer was not at all interested in the communist ideology and party politics. Borsi-Kálmán, Op. cit. , pp. 22-23.